WHY SPEED MATTERS!

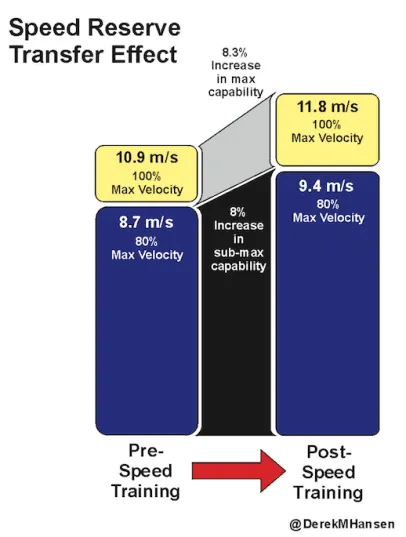

By increasing our maximal outputs we can increase our average sub-maximal outputs.

Therefore the exact same intensity of running speed POST speed adaptation will feel easier than it did previously = you can tolerate performing the old speed (pre-improvement) for longer. Now you have developed a larger speed reserve to tap into it.

It’s analogous in some ways to gaining muscle mass.

If you have more contractile tissue you will have a larger motor unit pool to recruit from to produce force, thus the same weights you once did POST muscular adaptation will now feel lighter.

Speed & Power Is Not Just For Athletes

One way to recruit fast-twitch (type IIb/x) muscle fibres is to contract a muscle rapidly and forcefully. Fast-twitch motor units have larger cross-sections and generate greater force per single motor unit than small twitch fibres. Also, the muscle shortening velocity of fast-twitch motor units is ~4x larger than slow-twitch muscle fibres.

So we can generate more force to facilitate maximal strength adaptations by moving rapidly and explosively. Doing this with a combination of sub-maximal, bodyweight and heavy loads is the combination that tends to work best.

Think INTENT TO MOVE THE BAR/WEIGHT (I’ve heard Christian Woodford say this about 100x working with him).

If you care about being powerful and quick and not just strong and big then the rate of force development and speed matters and can be concurrently trained in the weight training program.

Speed and power adaptations are very quickly and easily lost after a few weeks (strength and muscle size are typically much slower to lose in comparison).

All it takes to maintain some of these adaptations and even build them is a couple of sets at the beginning of your training session or in between rest periods (look up contrast/complex training for more).

This is a big component many traditional bodybuilders don’t do. This is fine if you don’t care about being explosive or athletic. But I do. This is why you see me doing ‘dynamic effort’ training above which is used in conjugate programming systems.

I commonly use this with my in-season athletes. I apply it to myself and encourage my clients to do it during warm-up sets to:

- Potentiate the nervous system for forthcoming heavier movements. This means we’re creating a temporary enhanced window to facilitate neuromuscular output.

- Promote an increased motor unit firing rate which is highest in maximal effort fast contractions.

- Retain fast-twitch fibre make-up and possibly shift a small amount of hybrid intermediate muscle fibres towards being more fast twitch.

We know a bigger muscle with a larger cross-sectional area certainly has more POTENTIAL to be strong and powerful. But only if you impose the demands necessary to elicit those power and speed adaptations.

Train slow – get slow.

Train quick – get quick.